By Mike Davey

Hamilton, Ontario — December 21, 2015 — Canada’s auto recyclers started something incredible in 2014 when industry partners banded together to clean up the Arctic and help Nunavut’s Arviat and Gjoa Haven communities establish sustainable models for dealing with hazardous vehicle waste. But they didn’t stop there. The project continued in 2015, this time targeting communities in the isolated region of Nunatsiavut.

Unlike urban and rural areas, many communities in the far north face significant challenges with effective vehicle recycling. Typically, end-of-life vehicles are simply piled up at the local dump. It’s a daunting task, but the Tundra Take-Back project proves that where’s there a will, there’s a way.

Volunteers from the recycling industry and Summerhill Impact flew into the communities of Nain and Hopedale in the fall of 2015 with one mission: teach local people the proper way to depollute vehicles, thereby preventing them from contaminating the local land and water sources.

Andrea Hoyt is the Environmental Assessment Manager with the Nunatsiavut Government, Department of Lands and Natural Resources. She notes that the logistics of the operation were challenging, but the results were well worth the effort.

“Shipping season is typically July to the end of November. At other times of year the pack ice in the Labrador Sea prevents ships from coming through,” she says. “It was a challenge, but there are great benefits. Community members got a chance to learn how to properly decontaminate vehicles, and it provided employment in addition to helping to clean up our communities.”

Jennifer Court is with Scout Environmental (formerly Summerhill Impact) and one of the volunteers with the team in Hopedale. She says that it’s not just a matter of the vehicles being unsightly. In Nain, the local dump is very close to the ocean. Contaminants leaching into the river can have a disastrous impact on the quality of life and health of the local people.

“Food is very expensive there,” she says. “Many of the Inuit people in those communities depend on fishing to supplement their food supply and to make a living, so it’s essential that the water remain uncontaminated.”

The tools used in Tundra Take-Back may not be what many auto recyclers are used to, but there’s no arguing with results.

“We did about 40 vehicles or so, depolluting them and then flattening them with an excavator,” says Darrell Pitman of P and G Auto. “The tools and equipment we used are staying in the communities, so the people we trained can continue the work on their own.”

The project will certainly continue, and there’s at least some chance that it will expand next year to include more communities.

“Long term, we’d like to run on a 10 year cycle,” says Hoyt. “The decontamination would continue on a regular basis, then the scrap metal would be shipped out every 10 years or so. Next year we’d like to see it expand to include the southern communities.”

Note that these communities are only “southern” by the standards of Nunatsiavut. They’re still relatively inaccessible, and cleaning up their local dumps would have just as big of an impact as it has in Nain and Hopedale.

It’s hard to overestimate the positive impacts from the Tundra Take-Back project. The goal of the project—removing potentially dangerous contaminants by recycling end-of-life vehicles—is laudable in and of itself. However, the positive impacts don’t stop there. There are both environmental and economic benefits that have been realized, and these will be ongoing.

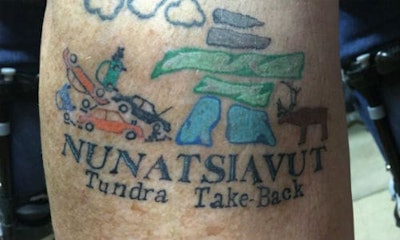

In short, automotive recyclers stepped up and helped the residents effect change in their communities, and it’s a two-way street. Judging by the tattoo on Darrell Pitman’s arm commemorating the trip, the communities changed them right back.